10,000 Birds Birds, Birding and Blogging

- Bird Guides of the World: David Casas Lopez, Colombiaby Editor on February 10, 2026 at 12:00 pm

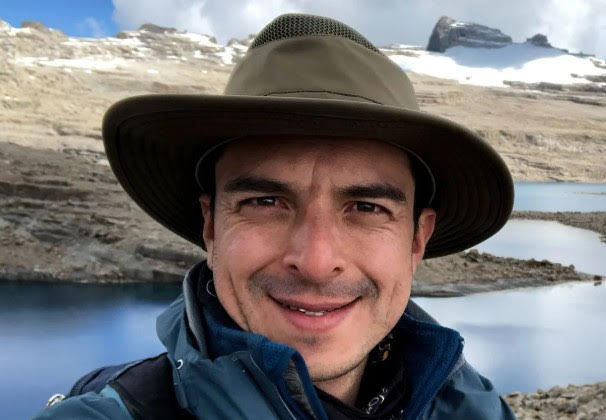

What is your favourite bird species?As a bird photography guide, I’ve grown attached to many different groups of birds. I admire the colours of Tanagers, the speed of Hummingbirds, the social behaviour of Parrots and Parakeets, the strength of Eagles, the voices of Antpittas, the mystery of Owls, the bold personalities of Toucans, and the fascinating feeding behaviour of Antbirds. In truth, I enjoy them all—but what I enjoy most is the challenge of photographing them in motion or in a perfect, expressive pose. Harpy Eagle What is your name, and where do you live?I’m David Casas Lopez, based in Bogotá, Colombia. I run Retorno Photo Tours, the first dedicated bird and wildlife photography tour company in the country. Collared Aracari What are the main regions or locations you cover as a bird guide?At Retorno Photo Tours, we cover a wide range of Colombian regions through 14 different tours scheduled around seasonal bird activity. Our main tours include:Emblematic Birds Tour (March–November):Focuses on the West and Central Andes—Antioquia, Risaralda, Caldas, Quindío, and Valle del Cauca—ideal for discovering many of Colombia’s most iconic birds.Colourful Birds Tour (December–February):Explores the Caribbean region, including the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (with 20+ endemics), La Guajira, and Serranía del Perijá.Iconic Birds Tour (November–March):Covers southern departments such as Huila, Cauca, and Putumayo, rich in Amazonian species.Majestic Birds Tour (March–October):Dedicated to the Chocó Bioregion near the Pacific coast, known for its exceptional biodiversity.We also run specialised tours: An Endemic Birds Tour, aiming for about 50 of Colombia’s ~75 endemics. The Dazzling Birds Tour, centred on Bogotá and its surroundings. A nationwide Hummingbirds Tour. Additionally, we organise targeted trips for species such as the Andean Bear, Harpy Eagle, Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock, Blue-bearded Helmetcrest, Green-bearded Helmetcrest, and others. Andean Cock-of-the-Rock How long have you been a bird guide?I’ve been leading tours for Retorno Photo Tours since 2021, but I began designing birdwatching and bird photography trips in 2018 for our parent company, Retorno Travel. Crescent-faced Antpitta How did you get into bird guiding?While designing birdwatching tours, I constantly needed high-quality photos to represent each region and species. After struggling to find the right images, I decided to take them myself. What started as a practical solution quickly became a passion, and eventually a career. This hands-on experience helps me understand exactly what bird photographers look for in the field. Rufous Motmot What aspects of being a bird guide do you like best? Which do you dislike most?I love helping visitors experience Colombia’s birdlife while also creating opportunities for local communities. Many areas in Colombia still struggle with poverty, deforestation, or the long-term effects of conflict. Bird tourism can offer sustainable jobs and encourage conservation, and seeing this impact on communities is deeply rewarding.The part I like least is simply that progress can feel slow. There is a lot of work to be done, and I wish positive change could happen faster. Red-headed Barbet What are the top 5–10 birds in your region that are the most interesting for visiting birders?Photographers especially enjoy: Eagles: including the Harpy Eagle, Black-and-Chestnut Eagle, and Ornate Hawk-Eagle. Hummingbirds: such as Helmetcrests, Coquettes, and Starfrontlets. Tanagers: including the Multicoloured Tanager, Gold-ringed Tanager, Scarlet-bellied Mountain Tanager, and Paradise Tanager. Cotingas: especially the Andean Cock-of-the-Rock and Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock. Antbirds: such as the Spot-backed Antbird and Ocellated Antbird. Rails: notably the endemic Bogotá Rail. Ducks: including the Torrent Duck. Screamers: like the Horned Screamer and Northern Screamer. Storks: especially the Jabiru. Antpittas: including the Chestnut-crowned Antpitta, Chestnut-naped Antpitta, Bicolored Antpitta, and Muisca Antpitta. Multicolored Tanager Can you outline at least one typical birdwatching trip? The Emblematic Birds Photography Tour – Coffee ZoneThis tour explores the central Andes, where cloud forest, valleys, and coffee farms support more than 800 bird species between 1,200 and 4,400 m. Key targets include the Multicoloured Tanager, Violet-tailed Sylph, and Yellow-eared Parrot. Over the course of the trip, photographers generally record more than 130 species. Itinerary (abbreviated): Day 0: Arrival in Medellín. Day 1–2 (San Rafael): White-mantled Barbet, Sooty Ant-Tanager (endemic), Tanagers, Barbets, Hummingbirds; travel to Jardín. Day 3 (Jardín): Oilbird, Red-bellied Grackle (endemic); travel to Mistrató. Day 4 (Mistrató): Black-and-Gold Tanager (endemic). Days 5–6 (Tatamá NP): Gold-ringed Tanager (endemic) and other cloud-forest specialities. Days 7–12 (Manizales, Chinchiná, Anaime): Grey-breasted Mountain-Toucan, Crescent-faced Antpitta, Buffy Helmetcrest, Bicoloured Antpitta, Brown-banded Antpitta, and multiple Tolima endemics (Yellow-eared Parrot, Tolima Blossomcrown, Tolima Dove, Colombia Chachalaca, Indigo-capped Hummingbird). Days 13–15 (Dagua & Valle del Cauca): Ruby-topaz Hummingbird, Glittering-green Tanager, Toucan Barbet, Spot-crowned Barbet, Chestnut Wood-Quail, Multicoloured Tanager. Day 16: Departure from Cali. White-bellied Antpitta What other suggestions can you give to birders interested in your area?For an Andean bird photography trip, we recommend lightweight, quick-drying clothing in natural colours, a wide-brimmed hat, a waterproof jacket, long pants, sturdy hiking boots, and rubber boots for wet areas. Sunscreen and insect repellent are essential, especially at altitude. Packing light but prepared will make the experience much more comfortable. Oilbird If any readers of 10,000 Birds are interested in birding with you, how can they best contact you?You can learn more or reach me directly through our website: www.retornophototours.com. You can contact us by email, via WhatsApp, or through the contact form on the site. We’d be happy to help you plan your Colombian bird photography trip Purple-backed Thornbill

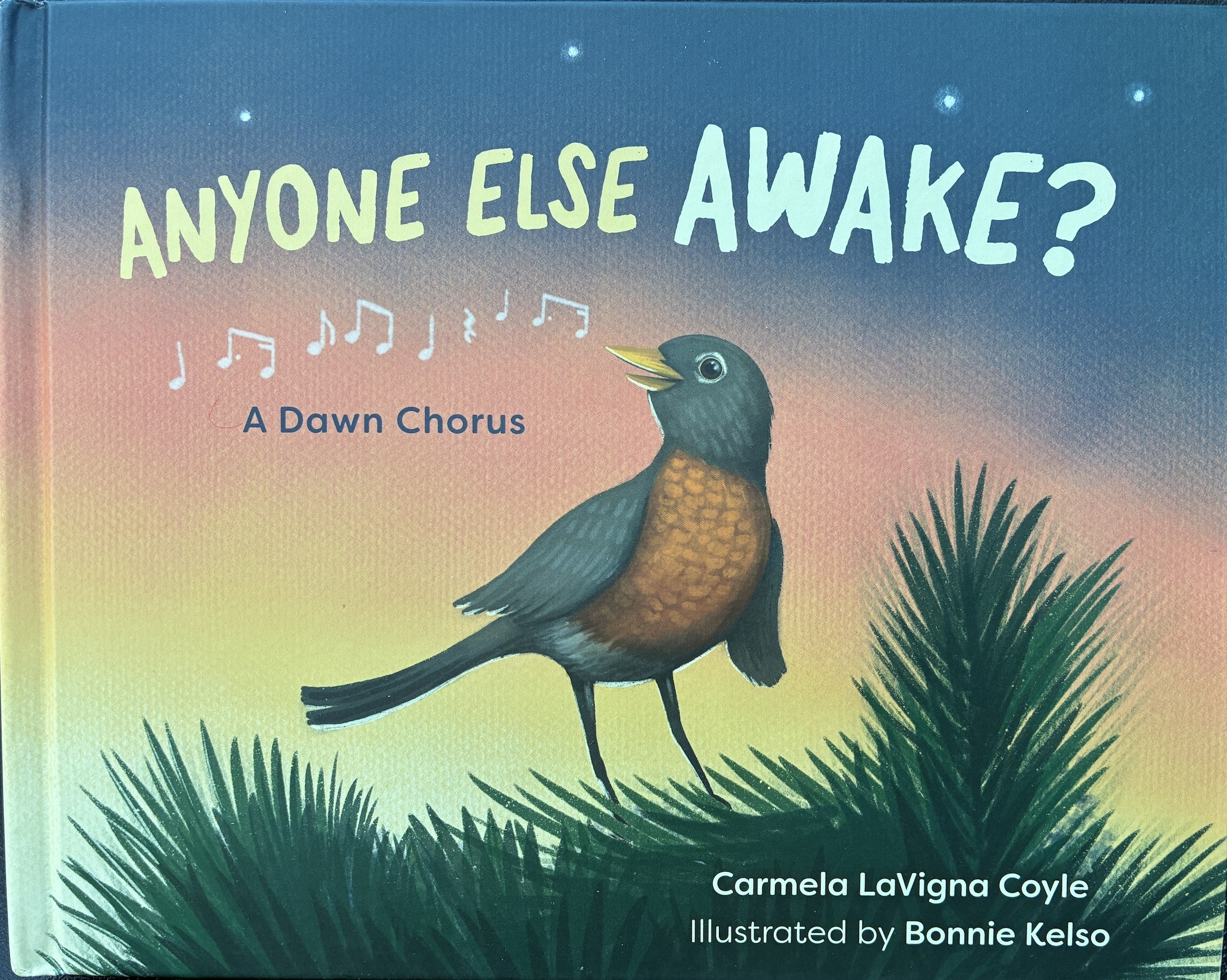

- Anyone Else Awake? A KidLit Bird Book Reviewby Susan Wroble on February 10, 2026 at 11:04 am

As spring approaches and the dawn swells with birdsong, you can introduce the youngest readers to the joys of listening to birds with the new picture book Anyone Else Awake? A Dawn Chorus. This nonfiction book, featuring common North American birds, is a gentle and lyrical introduction to the dawn chorus. Author Carmela LaVigna Coyle has brilliantly matched the rhythm and beat of each bird’s song to the reasons birds sing at dawn. As the book begins, a young girl wakes in the morning darkness and looks outside. From a treetop in her yard, a robin warbles: “Is… Is… Is anyone else awake?” A robin begins the dawn chorus by asking if anyone else is awake. Robins, with their large eyes and habit of roosting higher in trees, are one of the first birds to sing in the mornings, usually in the astronomical dawn. Carmela introduces the birds in the order in which they tend to join the chorus. When chickadee joins the chorus, the answer to robin’s question is “I am… I am.” In the book’s backmatter, readers learn of the three phases of dawn, marked by the position of the sun at 18° (astronomical dawn), 12° (nautical dawn) and 6° (civil dawn) below the horizon. “The Three Phases of Dawn” section of backmatter in ANYONE ELSE AWAKE. The chorus builds as first towhee and crow, dove and flicker, finch and geese, then pigeon and nuthatch all join in the morning song. The screech of a red-tailed hawk scatters the birds, and the book has a wordless spread of worry, as a single feather drifts down. Robin worriedly checks in: “Is everyone else all safe-safe-safe?” By the book’s end, the robin looks on from the fence as the girl asks the question: “Is anyone else awake? — and her family joins her, now awake. Chickadee, towhee, crow and flicker joining robin in the dawn chorus in the picture book ANYONE ELSE AWAKE? Carmela LaVigna Coyle has won numerous awards, and is best known for her “Do Princesses…” series of board and picture books that began with Do Princesses wear Hiking Books? Like Anyone Else Awake, Carmela’s other books focus on a love of the outdoors. She notes that even as a young child, she was fascinated by early morning birdsong. Later, she would often head out on a pre-dawn run, pausing to listen to the birds. Like Carmela, illustrator Bonnie Kelso brings her passion for animals and nature conservation to her work. A graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design, Bonnie was an exhibit designer for the Smithsonian before turning to book illustration. You can extend the reading of this book on Bonnie’s “Doodle Chats” YouTube channel, where kids (and adults) can follow Bonnie’s steps to learn todraw a robin like the one on the cover of Anyone Else Awake? Illustrator Bonnie Kelso demonstrating how to draw a robin like the one in ANYONE ELSE AWAKE? In the “Bird Talk” section of backmatter, the voice is from the birds themselves: “We loves visiting yards, playgrounds and parks.” This section touches on the need for fresh food and water, and the importance of turning off outdoor lights during migration. The “More Chatter About Birds” section of backmatter adds specific detail about birdsong. Some of the reasons that ornithologists believe that birds sing in the morning include staking a claim to territory, attracting mates, and declaring how fit and healthy they are! Carmela advises readers to listen for birdsong at the end of the day as well, when the birds are settling into their nests, roosts and tree cavities. While the age for this book is stated as from 4-8 years, it is such a delightful read-aloud that it is a good fit for even younger listeners. This would make a lovely addition to both preschool read-alouds and early elementary library programs. It would be a fabulous start of a collection of books to develop a lifelong love of birds. The illustration on the front and back pages of ANYONE ELSE AWAKE? with the birds featured in the book. Anyone Else Awake? A Dawn Chorus, written by Carmela LaVigna Coyle, illustrated by Bonnie Kelso, is published by Muddy Boots, 2026. ISBN: 978-1-4930-9057-0 32 pages, age 4-8

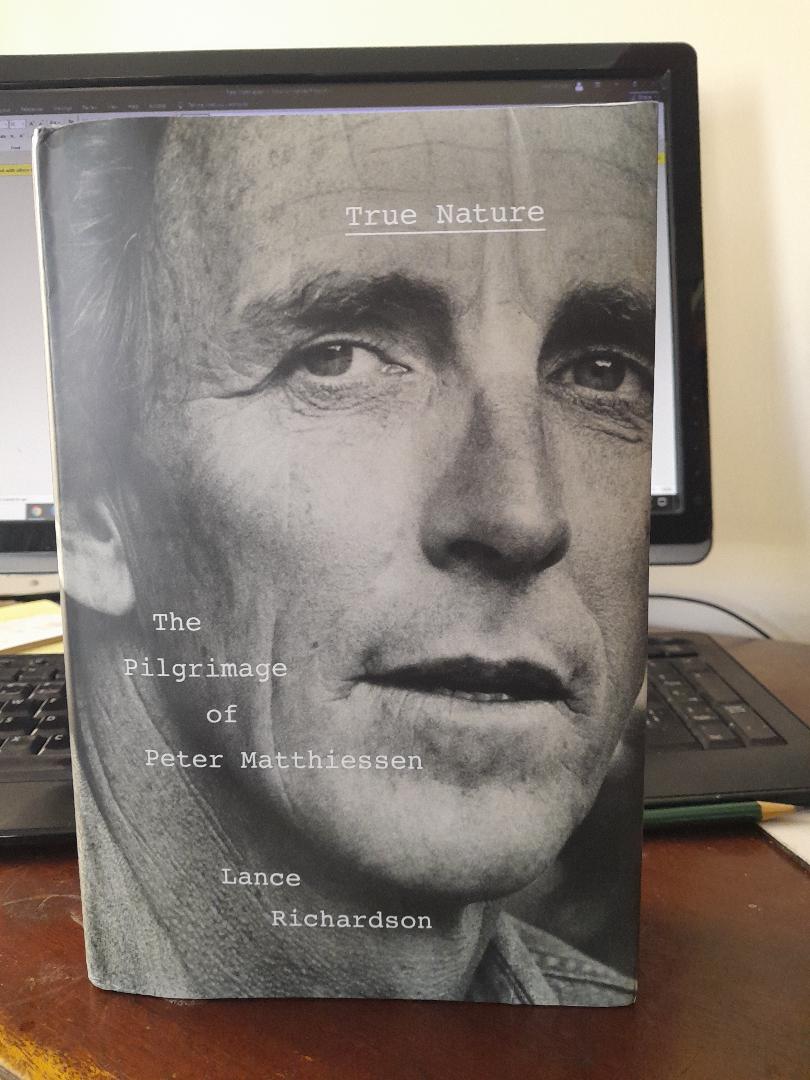

- Peter Matthiessen’s Pilgrimages: a book reviewby Mark on February 9, 2026 at 12:22 pm

Peter Matthiessen was peripatetic both in his travels and in his interests in flora and fauna of all kinds, including (among all else) reptiles, fish, birds, mammals. The latter form the backdrop for his 1978 tour de force book The Snow Leopard (he had, as well, a long obsession with the Bigfoot/Yeti which, if it exists, must surely be a mammal). The striped sea bass and the Long Island fishermen who seek them are the subject of Matthiessen’s Men’s Lives (1986); and reptiles (sea turtles, that is), play an oversize part in his great novel Far Tortuga (1975). And he was an avid birder, as well, starting in boyhood when he wore out multiple copies of his Peterson’s field guide. He was denied permission to enroll for an Ornithology class at Yale because he had never studied biology – until he drove to New Haven to convince the registrar, in person, of his birding prowess. (But he was an English major and, except for some college courses, had no formal training as a naturalist.) Later he published The Shorebirds of North America (1967) and The Birds of Heaven (2001), the latter of which chronicles his search for the world’s fifteen species of cranes. (In other words, that’s why Richardson’s new biography, True Nature: The Pilgrimage of Peter Matthiessen, merits a review on the 10,000 Birds blogsite.) Of patrician New York stock, Matthiessen grew up in material comfort but not unalloyed happiness — far from it: “I’ve been angry since I was about eight,” he said. Later in life, one of his groupies, a girl who worshipped him as a hero, said “he was really, probably, the unhappiest man I’ve ever met.” Six-foot two, charismatic and ruggedly handsome, he was what used to be called a man’s man. And he was quite the ladies’ man, too, for his whole life – a serial adulterer through three marriages. He was a lousy husband and a lousy father. He left his son Alex at home so he could go on the two-month expedition to Nepal that resulted in The Snow Leopard. Alex was eight years old at the time, and had recently lost his mother, Matthiessen’s second wife Deborah Love, to cancer. She became one of the subjects of The Snow Leopard (along with the snow leopard itself, of course). One might say, if so inclined, that the English novelist Evelyn Waugh (Brideshead Revisited, etc.) would have been completely unbearable as a human being were it not for his conversion to Roman Catholicism (the joke being that he was pretty unbearable anyway); and something similar could be said about Matthiessen and his adoption of Zen Buddhism as a lifelong pursuit. Another son, Luke, said that Zen helped his father – but it was also “a way of tuning everything else out . . . . a way of him escaping again.” Matthiessen wrote some thirty or so books, about a third of those fiction and the rest of them non-fictive accounts of his expeditions (all over the place), or social commentaries (he was a supporter of Cesar Chavez of the United Farmworkers’ movement in the nineteen-sixties, until Chavez turned on him; and in the nineteen seventies he went to bat for Leonard Peltier of the American Indian Movement, who was convicted, wrongfully, Matthiessen was convinced, of killing two FBI agents); or environmental rabble-rousing. But he was adamant, throughout his career, about wanting to be known as a novelist, not a nature writer. Richardson’s research into Matthiessen’s life and career appears impeccable. (Most impressive is that he retraced the same Snow Leopard steps Matthiessen took across the Himalayas to the Crystal Monastery in Nepal – a heroic journey back then, and now.) And he communicates the complexities of his subject well. You could put all of Matthiessen’s books on one pan of a balance scale, and Far Tortuga, in the other pan, would outweigh them all. I guess it’s my favorite book in all the world. It does not appear on the Modern Library’s list of “One Hundred Best Novels of the Twentieth Century” nor (presumably – I haven’t checked) any other such list. That is inexplicable. It should be in the top eight or ten. Or maybe two, alongside Ulysses. It’s a story about turtle fishermen in the Cayman Islands, narrated mostly in pidgin dialect and dialogue, infused with atmospherics of West Indian Zen. Birds don’t play much of a part in the book, other than in the very last line: “bird cry and thundering / black beach / a figure alongshore, and white birds towarding” (whatever that means), and which, in context, will hit you like a sledgehammer to the chest – in a good way, I mean. So that’s the other reason why this new biography of a flawed, tortured, selfish man who wrote a magnificent, sublime, astounding book merits a review on the 10,000 Birds blogsite. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ True Nature: The Pilgrimage of Peter Matthiessen. By Lance Richardson. Pantheon, New York. 709 pp., $40.

- Birding Kraeng Krachan National Park, Thailand (Part 1)by Kai Pflug on February 9, 2026 at 12:00 pm

Kaeng Krachan is the largest national park in Thailand, and Wikipedia also claims it is a popular park owing to its proximity to the tourist town of Hua Hin. Frankly, I cannot confirm that – at least on weekdays, it sometimes seemed the only tourists in the park were a few guests of the Baan Maka Nature Lodge, where I stayed as well. But maybe it was the wrong season (it tends to be, wherever and whenever I go birding). Anyway, the park was still quite productive for me, mostly due to the help of competent bird guides from the lodge (without such guides, I would probably have given up birding long ago and started a more fruitful hobby, such as knitting sweaters, carving soap bars, or learning to play air guitar). Without them, I would not have found any broadbills at all, though regrettably, I still missed my major target, the Dusky Broadbill (which looks a bit like a hybrid between a broadbill and a frogmouth – so, a very attractive bird). But I did see a Banded Broadbill, a bird that the HBW rather vaguely calls “remarkable-looking”. The males (at least in Thailand) have a narrow black band across the upper breast, which the females lack. A nice report on a nesting pair of these broadbills, along with good photos, can be found here. The second broadbill I saw was a Silver-breasted Broadbill. The HBW calls it “one of Southeast Asia’s most iconic forest birds”. The silky-white line across the breast indicates that this is a female. No such gender distinctions are available for the Blue-eared Barbet. Have you ever had to stop an outdoor conversation because the cicadas were too loud? Birds like this barbet do the same – but only if the bird vocalized in a frequency band completely overlapped by the cicada noise, and the cicada noise saturated the majority of that frequency band (source). (If you have trouble imagining the cicada scenario, transfer it into a discotheque with very loud music, but please do not take the poor bird along). If you dislike the idea of a barbet with a blue ear, evolution has provided an alternative: the Green-eared Barbet. The authors of the HBW entry for the species seem to be a bit frustrated by it: “Seems generally difficult to locate, probably because it favours canopy of evergreen forest, where not easy to detect.” And they are probably not even photographers. Possibly the most beautiful bird I saw at Kaeng Krachan was a Black-backed Dwarf Kingfisher. Apparently, somebody had found a burrow of a nesting pair and set up a little hide in front of it. Fortunately, this did not keep the parents from bringing all kinds of interesting little lizards to their (invisible) chicks. (Unnecessary editorial note: Grammarly always wants me to delete the word “apparently” in sentences such as the above. Presumably, it thinks the word makes me seem weak and indecisive, while I like it exactly for its implication of vagueness and uncertainty. End of unnecessary editorial note). By now, I have seen the Asian Fairy Bluebird in at least four, probably five, different countries, but I still haven’t gotten a satisfying photo of it. Unfortunately, the visit to Kaeng Krachan did not change this. Instead, I somewhat unexpectedly (given the name of the bird) saw a Chinese Francolin … … a rather vocal male calling from a relatively exposed tree perch, indicating its expert knowledge of acoustics. I did not see many raptors at Kaeng Krachan. One I did see was a Crested Serpent-eagle, a very common raptor in large parts of Southeast Asia as well as China and India. The other was the Black-thighed Falconet, one of the 5 falconets in the well-named genus Microhierax (“small falcon”). Given that I saw the species in this little group of three birds, I found this part of the HBW species profile interesting: “Feeds communally, with up to four falconets eating from single prey item; communal hunting and feeding may be important for young to learn which insects are suitable prey.” So, maybe I watched a kindergarten there? In cuteness, these little raptors are matched by the Barred Buttonquails, which seem to be fairly common in the farmland close to the national park. They share their habitat with the Indochinese Bushlark. Its scientific name Plocealauda erythrocephala indicates that the bird is red-headed (erythros red; kephalos -headed) – false advertising, if you ask me. While these bushlarks can be difficult to see unless moving, they are no match for the camouflage of the Blue-winged Leafbird. “BE THE LEAF!” In the “Other” section of this post, there are a few reptiles and mammals – one looking ok, the other extremely ugly (hint: not the deer but the one looking like Charles Manson in a Halloween costume). Part two covering Kaeng Krachan NP will have much nicer photos – of butterflies.

- Birding Lodges of the World: Inala Country Accommodation, Australiaby Editor on February 9, 2026 at 12:00 pm

Which bird species do you think is the biggest attraction to visitors of your lodge (please only name one species)? Forty-spotted Pardalote (Pardalotus quadragintus) must be at the top of the list. It’s endemic to SE Tasmania, and Inala is home to a thriving colony. You can look for this tiny bird with its snazzy white dots from a specially constructed platform on the reserve. If you’re lucky, you might even be able to count the spots! Forty-spotted Pardalote (photo: A. Browne) What is the name of your lodge, and since when has your lodge been operating? We’re called Inala Country Accommodation and Inala Nature Tours. We’ve been operating for more than 30 years. How best to travel to your lodge? We’re on South Bruny Island off Australia’s island state of Tasmania. So we’re on an island off an island off an island. We’re only about a two-hour drive from Hobart, with a short ferry ride in the middle. The ferry ride is just 15 minutes across the scenic D’Entrecasteaux Channel, and it might give you a chance to tick some seabirds, including Silver Gull, Kelp Gull, Greater Crested Tern, Australasian Gannet, and Black-faced Cormorant. Once you get to Bruny Island, head south. You’ll see glorious scenery on the way. Tasmania is known for its beautiful landscapes and great fresh produce, and Bruny Island has some of the best of both! No car? No problem. We can arrange transfers from Hobart. White-bellied Sea-eagle (photo: C. Davidson) What kind of services – except for accommodation and food – does your lodge offer to visiting birders? There are two lovely self-catering cottages on the property. We offer 3-hour guided walking tours of the reserve and full-day or multi-day tours of Bruny Island and bird hides, including a hide specially designed for photographing raptors. We also offer night tours to view some of Tasmania’s special mammals and to watch Short-tailed Shearwaters returning to their burrows during the summer breeding season. What makes your lodge special? We have a 1,500-acre nature reserve with walking tracks that cover a range of habitats from tall forest to heathland and grassland, as well as ponds and lakes. It is also an important breeding area for the critically endangered Swift Parrot, which migrates annually across Bass Strait. Native mammals such as Tasmanian Pademelons, Bennett’s Wallabies, and Common Brushtail Possums can also easily be found here. Bennett’s Wallaby (photo: C. Davidson) What are the 10 – 20 most interesting birds that your lodge offers good chances to see? Inala is home to all 12 Tasmanian endemic bird species, including Forty-spotted Pardalote, Yellow Wattlebird, Green Rosella, and Tasmanian Nativehen (known locally as the Turbo-chook). We often receive visits from a range of raptors, including the stunning pure white morph of the Grey Goshawk and the White-bellied Sea-eagle. (Don’t forget to look up for a chance of the Tasmanian subspecies of Wedge-tailed Eagle!) Grey Goshawk (photo: A. Browne) What is the best time to visit your lodge, and why?The birds are out and about and shaking their tail feathers in the Austral Spring (October – December), but Summer and Autumn offer beautiful weather along with birds and wildflowers. The endemics are present all year round. Superb Fairywren (photo: C. Davidson) Is your lodge involved in conservation efforts? If yes, please describe them. Inala Nature Reserve was set up to conserve the endangered Forty-spotted Pardalote, and we work with researchers at the Australian National University to understand the biology and ecology of this endemic species. We have also been involved in Swift Parrot research since the 1990s. We have been propagating and planting trees, particularly for these species, which also provide food and shelter for a wide range of local birds, mammals, and invertebrates. We are also involved in plant conservation, including ex situ projects for rare and endangered plants such as the Mulanje Cedar (Widdringtonia whytei) from Malawi, and endemic mountaintop species from Far North Queensland. We also grow Wollemi Pine as part of a global metacollection. We work with botanic gardens around the world as part of the Global Genome Initiative, helping to record and preserve the genetic diversity of the world’s flora. Pink Robin (photo: C. Davidson) What other suggestions can you give to birders interested in visiting your lodge? Bring your usual birding kit—binoculars, scope, and camera. The cottages are fully equipped for self-catering, and there are some options for eating out on the island. There’s no public transport on the island. We recommend booking accommodation and any tours well in advance to avoid disappointment. Do you have activities for non-birders? If so, please describe. The reserve is a lovely spot for walking and experiencing nature on our lovely walking tracks. There’s no need to focus solely on the birds (unless you want to!) because there’s a lot of other wildlife on the property. We have a botanical garden dedicated to the plant species of Gondwana. It contains more than 750 species of 50 families that trace their ancestry back to the time of the dinosaurs. We also have a small nature museum. If you want to roam further afield, some delightful beaches are only a short drive away. Black Currawong (photo: C. Davidson) If any reader of 10,000 Birds is interested in staying at your lodge, how can they best contact you? You can contact us through our website (https://inalanature.com.au/). You can also read about our tours, our conservation work, and a lot more on our site. Lodge and environmental photos by B. Moriarty

BirdWatching Your source for becoming a better birder

- You’re Probably Calling This Bird the Wrong Nameby Madavor Media on February 8, 2026 at 12:19 pm

One of the most surprising things new birdwatchers discover is how often common birds are misnamed. Even people who have watched birds casually for years … Read More “You’re Probably Calling This Bird the Wrong Name”

- These Are the 20 Birds Most People in the US See Every Dayby Madavor Media on February 7, 2026 at 1:43 pm

Birds are one of the few wild animals most people encounter daily. They hop across lawns, perch on fences, gather in parking lots, and call … Read More “These Are the 20 Birds Most People in the US See Every Day”

- It’s Not Magic: How Birds Really Know When the Feeder Is Fullby Madavor Media on February 2, 2026 at 7:07 am

You top up the bird feeder, step back inside… and within minutes birds seem to appear out of nowhere. It can feel almost magical as … Read More “It’s Not Magic: How Birds Really Know When the Feeder Is Full”

- 10 Birds That Look Fake But Are Actually Realby Madavor Media on January 3, 2026 at 6:44 pm

At first glance, these birds do not look real. Their colors feel too bright. Their patterns look artificial. Some seem more like toys, cartoons, or … Read More “10 Birds That Look Fake But Are Actually Real”

- Why Birds Suddenly Go Silent at Certain Times of Dayby Madavor Media on January 2, 2026 at 4:52 pm

You step outside expecting birdsong and instead, there’s nothing. No chirping. No calls. No background chorus. It can feel eerie, even worrying. But when birds … Read More “Why Birds Suddenly Go Silent at Certain Times of Day”